Tattooing is among identified risk factor for blood-borne diseases.

ObjectiveThis study aims to determine the prevalence of tattooing during lifetime and in prisons and its related factors among Iranian prisoners.

MethodsThis is a cross-sectional study. The required data was obtained from hepatitis B and C surveillance surveys in prisons in 2015–2016 that was collected through face-to-face interview. 12,800 prisoners were selected by multi-stage random sampling from 55 prisons of 19 provinces in Iran. Weighted prevalence and associated factors (using Chi-Square test and multivariate logistic regression) were determined by Stata/SE 14.0 survey package.

ResultsOut of 12,800 prisioners, 11,988 participated in the study (93.6% participation rate). The prevalence of tattooing in lifetime and in prisons was 44.7% and 31.1% respectively. The prevalence of tattooing during lifetime was significantly associated with age<35 years, being single, illiteracy, history of imprisonment, drug use, piercing during lifetime, extramarital sex and history of STI; the prevalence of tattooing in prison had a significant association with history of imprisonment, drug use, piercing in prison, and history of extramarital sex (p<0.05).

Study limitationsInformation and selection bias was one of the study limitations.

ConclusionThe results of this study showed that the prevalence of tattooing during lifetime and in prison among prisoners was significantly high especially in high-risk groups such as drug users and sexually active subjects. Given the role of tattooing, drug injection and sex in the transmission of blood-borne diseases, harm reduction programs are recommended to reduce these high-risk behaviors in prisons.

Tattooing has become prevalent; increased tendency of individuals for tattooing cannot be ignored.1 Tattooing refers to the practice of injecting ink into the skin using a special tool to create a permanent or long-lasting image, design or word2 usually associated with skin penetration, pain and bleeding. Tattoo is used for a wide range of purposes such as clinical and medical reasons, affiliation with particular gangs or religious groups, tending to be beautiful, attracting the attention of the opposite sex, curiosity, art and fashion.3–6

Clinics, tattooing halls, homes, and prison are among the places where tattooing takes place.1 Tattooing is a common phenomenon among prisoners. A cross-sectional assess in most international studies in 2009 shows that more than 55% of prisoners in different countries7–10 and 45% of Iranian prisoners11 have tattoos. The results of studies conducted in African12 and European countries13 reveal that the prevalence of tattooing in prisons is 67% and 45%, respectively. Also, many studies have been conducted on tattooing and related factors in various populations, often in adolescents and young people.14–16 However, fewer studies have examined this high-risk behavior in a high-risk group such as prisoners. These few studies show that tattooing in prison is associated with high-risk behaviors such as history of drug injection, injection in prison, history of shared injection, sex in prison, and multiple sex partners.17,18

It is important to examine tattooing in prisons in terms of infectious reactions. The results of studies indicate that there is a significant relationship between prevalence of Blood-Borne Diseases (BBD) such as HIV, HBV and HCV and tattooing in prisons.17,19,20 Due to the ban on tattooing in prisons, followed by lack of facilities and equipment, it is usually done through non-sterile and unhygienic instruments12,21 by non-professionals. Studies illustrate that the odds of infliction with BBD in non-professional tattooing is 3.25 times higher than that in professional tattooing.22 Also, tattooing is more common among Prisoners Who Inject Drugs (PWID).17 In line with this, needle sharing is one of the most important ways of transmitting BBD in many countries, including Iran.23–25 Therefore, the high prevalence of tattooing among inmates and in prison has led to an increase in the burden of BBD in prisons and, as prisoners ultimately are released and come back to the community, the burden of these diseases in society increases. In this regard, determining the prevalence of tattooing and its predictors among Iranian prisoners, from which no information exists about the prevalence of tattooing in prison in order to design biobehavioral surveillance plans and implementing appropriate interventions in prisons is important. This study aims to determine the prevalence of tattooing during lifetime and in prisons as well as its related factors among Iranian prisoners in 2015 and 2016.

MethodsThe present cross-sectional descriptive-analytical study is part of the hepatitis B and C surveillance surveys in Iranian prisons that was conducted during 2015 and 2016. This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kurdistan University of Medical Science with the ethic code MUK.REC.1395.280.

Multistage random sampling was used in both study periods. First, 31 provinces of Iran were divided into 3 categories (north, center, and south). Then, 3 provinces from each category, and 2–4 prisons from each province were randomly selected. In total, 19 provinces and 55 prisons were selected for both study periods. The number of samples allocated for each province and each prison was determined based on the average annual population of prisoners in each province and prison through probability-proportional-to-size sampling method. In the next step, using a roster of prisoners, 12,800 Iranian prisoners of at least 18 years of age with at least one month's period of imprisonment at the time of the study were selected by systematic sampling. Finally, the subjects were participated in the study by providing an informed consent form.

The required information was collected through face-to-face questionnaire-based interview by trained interviewers. The questionnaire had sections such as: demographic characteristics, history of imprisonment, history of drug use, tattooing and piercing, sexual behavior patterns, and history of Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD). Validity and reliability of the questionnaire had been confirmed in 2009.11

In order to increase the spatial and temporal integration and comparison capability of data collected in different periods, the survey program was implemented at the same time each year. In addition, the sampling process was performed uniformly using R 3.2.1 sampling package with the following command:

Cluster (data, clustername, size, method=c (“srswor”, “srswr”, “prison”, “systematic”), pik, description=FALSE).

The following measures were taken to maintain the ethics in this study: referring to prisons on specific dates and with prior coordination to do interviews, conducting interviews in a safe and confidential place in the prison, introducing the interviewer and the objectives of the study in plain language at the beginning of each interview, obtaining written informed consent from subjects willing to participate in the study, granting the right to the participants to leave the interview, assigning a specific code to each prisoner in the questionnaire instead of writing the prisoner's name.

The analyses were performed using the Stata/SE 14.0 survey package. Weighted prevalence of tattooing during lifetime and in prison in each subgroup of prisoners were estimated. Weighting was based on the post-stratification method and the post-weight instrument, and the frequency distribution of post-strata was determined using information about the willingness of subjects to participate in the study. Chi-Square test was used to determine the relationship between each qualitative variable with the response variables (Tattooing in lifetime: a history of having any tattoo at any time of life and any place. Tattooing in prison: a history of having any tattoo at prison). In addition, multivariate logistic regression was used to estimate the final model based on variables with p<0.2 in the chi-square test and to calculate the Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR). All analyses related to history of tattooing in prisons were limited to those who had a history of tattooing during their lifetime.

ResultsFrom 12,800 prisoners, 11,988 inmates (5507 prisoners in 2015 and 6481 prisoners in 2016) with the mean age 35.7±9.7 years participated in the study (93.6% participation rate). The frequency distribution of demographic and behavioral variables is presented in table 1.

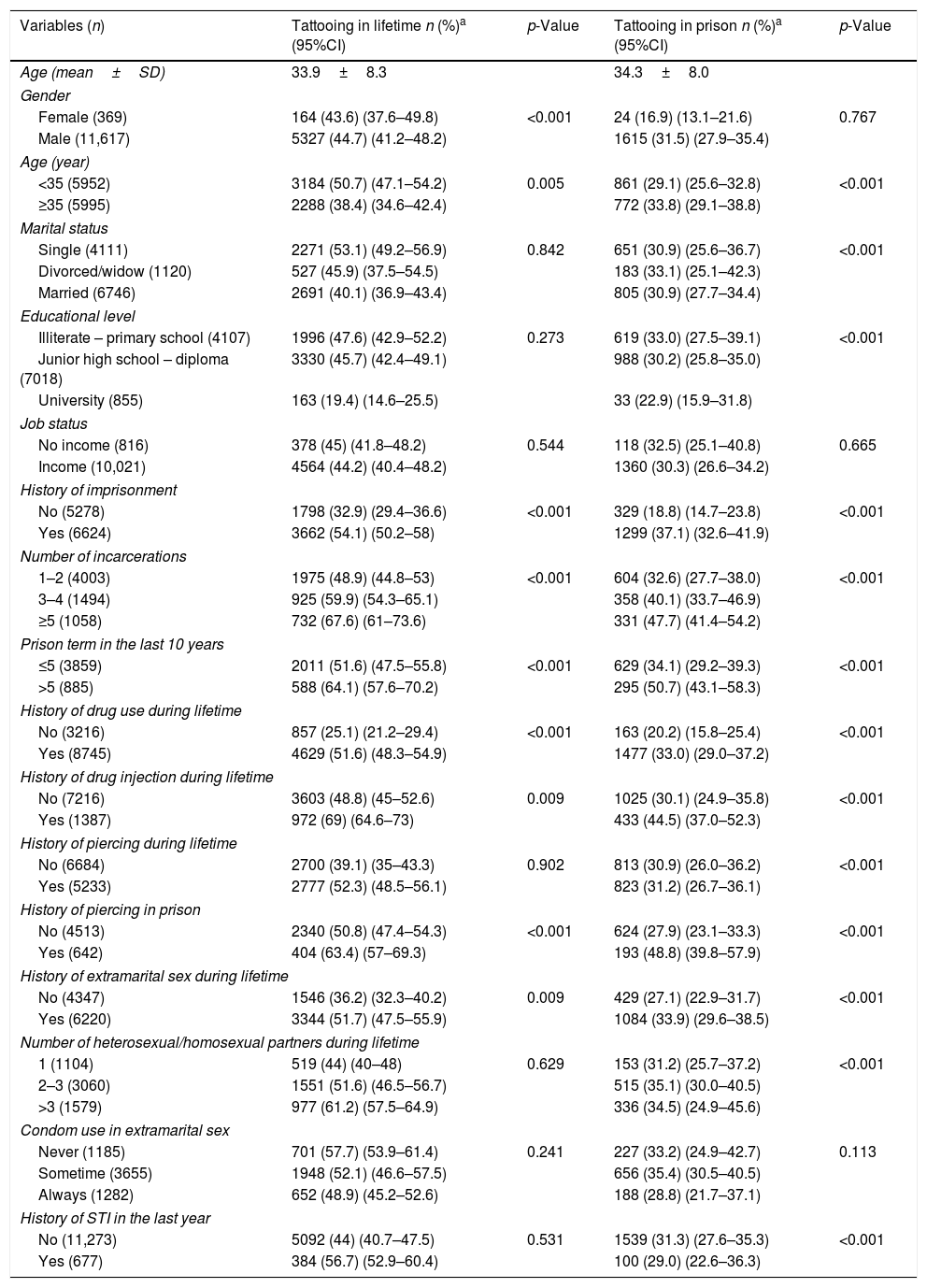

Prevalence of tattooing during lifetime and in prison in sub groups of Iranian prisoners, 2015–2016.

| Variables (n) | Tattooing in lifetime n (%)a (95%CI) | p-Value | Tattooing in prison n (%)a (95%CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) | 33.9±8.3 | 34.3±8.0 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female (369) | 164 (43.6) (37.6–49.8) | <0.001 | 24 (16.9) (13.1–21.6) | 0.767 |

| Male (11,617) | 5327 (44.7) (41.2–48.2) | 1615 (31.5) (27.9–35.4) | ||

| Age (year) | ||||

| <35 (5952) | 3184 (50.7) (47.1–54.2) | 0.005 | 861 (29.1) (25.6–32.8) | <0.001 |

| ≥35 (5995) | 2288 (38.4) (34.6–42.4) | 772 (33.8) (29.1–38.8) | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single (4111) | 2271 (53.1) (49.2–56.9) | 0.842 | 651 (30.9) (25.6–36.7) | <0.001 |

| Divorced/widow (1120) | 527 (45.9) (37.5–54.5) | 183 (33.1) (25.1–42.3) | ||

| Married (6746) | 2691 (40.1) (36.9–43.4) | 805 (30.9) (27.7–34.4) | ||

| Educational level | ||||

| Illiterate – primary school (4107) | 1996 (47.6) (42.9–52.2) | 0.273 | 619 (33.0) (27.5–39.1) | <0.001 |

| Junior high school – diploma (7018) | 3330 (45.7) (42.4–49.1) | 988 (30.2) (25.8–35.0) | ||

| University (855) | 163 (19.4) (14.6–25.5) | 33 (22.9) (15.9–31.8) | ||

| Job status | ||||

| No income (816) | 378 (45) (41.8–48.2) | 0.544 | 118 (32.5) (25.1–40.8) | 0.665 |

| Income (10,021) | 4564 (44.2) (40.4–48.2) | 1360 (30.3) (26.6–34.2) | ||

| History of imprisonment | ||||

| No (5278) | 1798 (32.9) (29.4–36.6) | <0.001 | 329 (18.8) (14.7–23.8) | <0.001 |

| Yes (6624) | 3662 (54.1) (50.2–58) | 1299 (37.1) (32.6–41.9) | ||

| Number of incarcerations | ||||

| 1–2 (4003) | 1975 (48.9) (44.8–53) | <0.001 | 604 (32.6) (27.7–38.0) | <0.001 |

| 3–4 (1494) | 925 (59.9) (54.3–65.1) | 358 (40.1) (33.7–46.9) | ||

| ≥5 (1058) | 732 (67.6) (61–73.6) | 331 (47.7) (41.4–54.2) | ||

| Prison term in the last 10 years | ||||

| ≤5 (3859) | 2011 (51.6) (47.5–55.8) | <0.001 | 629 (34.1) (29.2–39.3) | <0.001 |

| >5 (885) | 588 (64.1) (57.6–70.2) | 295 (50.7) (43.1–58.3) | ||

| History of drug use during lifetime | ||||

| No (3216) | 857 (25.1) (21.2–29.4) | <0.001 | 163 (20.2) (15.8–25.4) | <0.001 |

| Yes (8745) | 4629 (51.6) (48.3–54.9) | 1477 (33.0) (29.0–37.2) | ||

| History of drug injection during lifetime | ||||

| No (7216) | 3603 (48.8) (45–52.6) | 0.009 | 1025 (30.1) (24.9–35.8) | <0.001 |

| Yes (1387) | 972 (69) (64.6–73) | 433 (44.5) (37.0–52.3) | ||

| History of piercing during lifetime | ||||

| No (6684) | 2700 (39.1) (35–43.3) | 0.902 | 813 (30.9) (26.0–36.2) | <0.001 |

| Yes (5233) | 2777 (52.3) (48.5–56.1) | 823 (31.2) (26.7–36.1) | ||

| History of piercing in prison | ||||

| No (4513) | 2340 (50.8) (47.4–54.3) | <0.001 | 624 (27.9) (23.1–33.3) | <0.001 |

| Yes (642) | 404 (63.4) (57–69.3) | 193 (48.8) (39.8–57.9) | ||

| History of extramarital sex during lifetime | ||||

| No (4347) | 1546 (36.2) (32.3–40.2) | 0.009 | 429 (27.1) (22.9–31.7) | <0.001 |

| Yes (6220) | 3344 (51.7) (47.5–55.9) | 1084 (33.9) (29.6–38.5) | ||

| Number of heterosexual/homosexual partners during lifetime | ||||

| 1 (1104) | 519 (44) (40–48) | 0.629 | 153 (31.2) (25.7–37.2) | <0.001 |

| 2–3 (3060) | 1551 (51.6) (46.5–56.7) | 515 (35.1) (30.0–40.5) | ||

| >3 (1579) | 977 (61.2) (57.5–64.9) | 336 (34.5) (24.9–45.6) | ||

| Condom use in extramarital sex | ||||

| Never (1185) | 701 (57.7) (53.9–61.4) | 0.241 | 227 (33.2) (24.9–42.7) | 0.113 |

| Sometime (3655) | 1948 (52.1) (46.6–57.5) | 656 (35.4) (30.5–40.5) | ||

| Always (1282) | 652 (48.9) (45.2–52.6) | 188 (28.8) (21.7–37.1) | ||

| History of STI in the last year | ||||

| No (11,273) | 5092 (44) (40.7–47.5) | 0.531 | 1539 (31.3) (27.6–35.3) | <0.001 |

| Yes (677) | 384 (56.7) (52.9–60.4) | 100 (29.0) (22.6–36.3) | ||

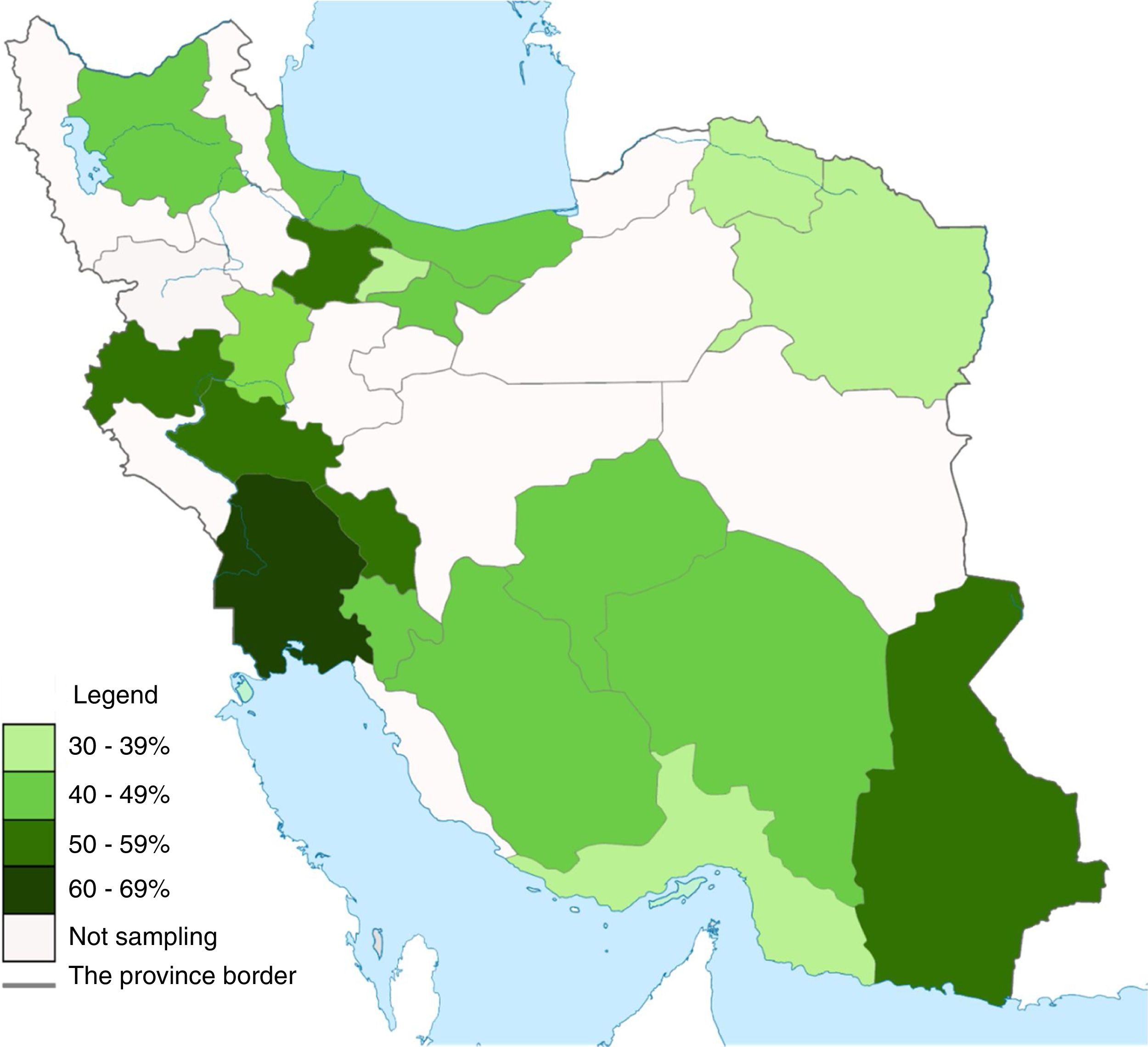

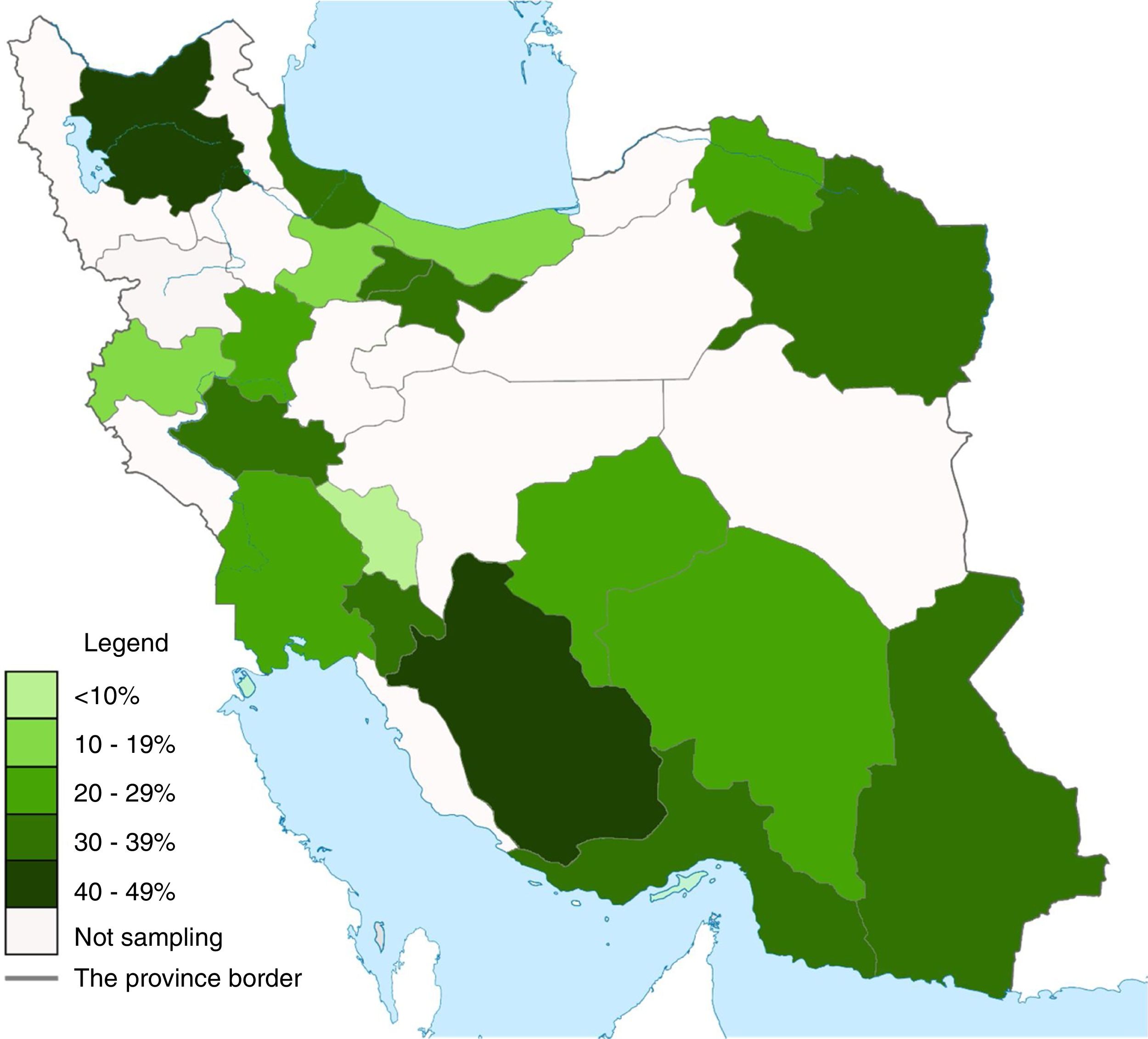

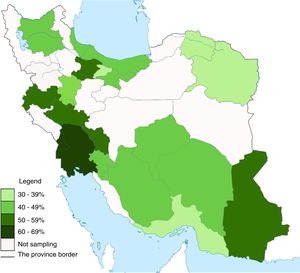

The prevalence of tattooing in lifetime among prisoners was 44.7% (95% CI: 41.3–48.1%) and the prevalence of tattooing in prisons among inmates with a history of tattooing was 31.1% (95% CI: 27.4%–35.0%). The prevalence of tattooing in lifetime and in prison in the studied provinces varied from 33.3% to 61.4% (Fig. 1) and from 9.9% to 44.5% (Fig. 2), respectively, and these differences were statistically significant (p<0.05). A number of 3053 (56.2%) tattooing among prisoners was done by friends, 1198 (22.3%) by inmates, 635 (12.8%) by subjects themselves, 170 (3.2%) by family members, 153 (2.8%) by peddlers and 155 (2.7%) cases by barbers.

Analysis in the subgroups of prisoners showed that the prevalence of tattooing both in lifetime and in prison was significantly higher in subjects with a history of imprisonment than those without any incarceration, in prisoners with more than 5 times imprisonment than those with 1–2 times, in individual with prison term>5 years than those with≤5 years, in drug users than non-drug users, in PWID compared to non-injection drug users, in inmates with a history of piercing in prison than those with no history, and in individuals with extramarital sex than those with no non-marital sex (p<0.05). In addition, the prevalence of tattooing during lifetime was higher in prisoners with age less than 35 years while the prevalence of tattooing in prison was higher in inmates with age 35 years and up (p<0.05) (Table 1).

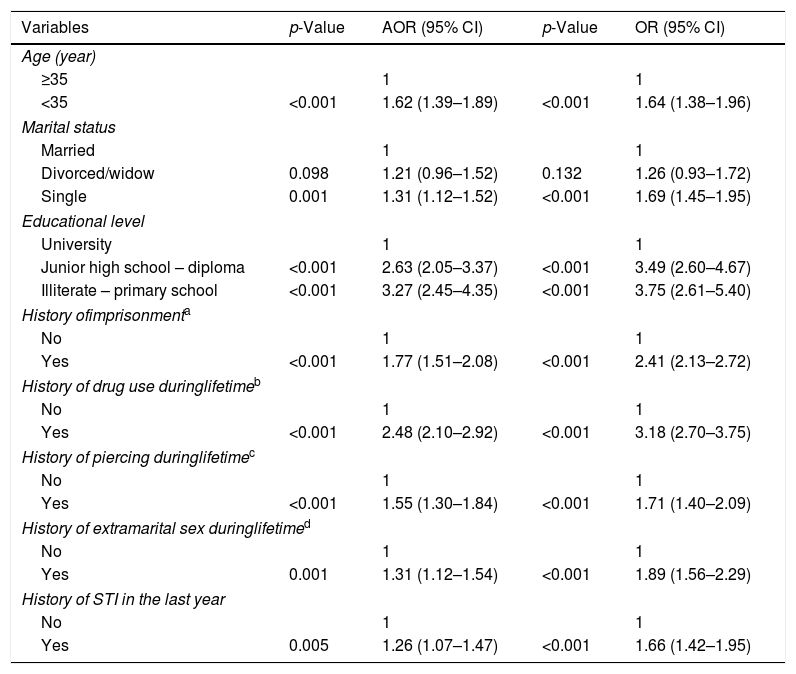

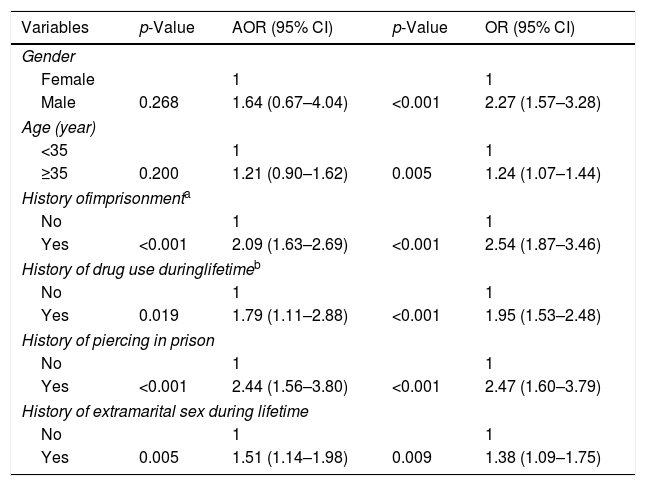

Based on multivariate logistic regression, the prevalence of tattooing in lifetime is significantly associated with age less than 35 years (AOR=1.62, 95% CI: 1.39, 1.89), being single (AOR=1.31, 95% CI: 1.12, 1.52), illiteracy (AOR=3.27, 95% CI: 2.45, 4.35), history of imprisonment (AOR=1.77, 95% CI: 1.51, 2.08), history of drug use (AOR=2.48, 95% CI: 2.10, 2.92), history of piercing in lifetime (AOR=1.55, 95% CI: 1.30, 1.84), and history of extramarital sex (AOR=1.31, 95% CI: 1.12, 1.54) and history of STI (AOR=1.26, 95% CI: 1.07, 1.47) (Table 2) and the prevalence of tattooing in prison has a significant association with history of imprisonment (AOR=2.09, 95% CI: 1.63, 2.69), history of drug use (AOR=1.79, 95% CI: 1.11, 2.88), history of piercing in prison (AOR=2.44, 95% CI: 1.56, 3.80), and history of extramarital sex in lifetime (AOR=1.51, 95% CI: 1.14, 1.98) (Table 3).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors associated with history of tattooing during lifetime among prisoners in 2015 and 2016.

| Variables | p-Value | AOR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | ||||

| ≥35 | 1 | 1 | ||

| <35 | <0.001 | 1.62 (1.39–1.89) | <0.001 | 1.64 (1.38–1.96) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 1 | 1 | ||

| Divorced/widow | 0.098 | 1.21 (0.96–1.52) | 0.132 | 1.26 (0.93–1.72) |

| Single | 0.001 | 1.31 (1.12–1.52) | <0.001 | 1.69 (1.45–1.95) |

| Educational level | ||||

| University | 1 | 1 | ||

| Junior high school – diploma | <0.001 | 2.63 (2.05–3.37) | <0.001 | 3.49 (2.60–4.67) |

| Illiterate – primary school | <0.001 | 3.27 (2.45–4.35) | <0.001 | 3.75 (2.61–5.40) |

| History ofimprisonmenta | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | <0.001 | 1.77 (1.51–2.08) | <0.001 | 2.41 (2.13–2.72) |

| History of drug use duringlifetimeb | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | <0.001 | 2.48 (2.10–2.92) | <0.001 | 3.18 (2.70–3.75) |

| History of piercing duringlifetimec | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | <0.001 | 1.55 (1.30–1.84) | <0.001 | 1.71 (1.40–2.09) |

| History of extramarital sex duringlifetimed | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.001 | 1.31 (1.12–1.54) | <0.001 | 1.89 (1.56–2.29) |

| History of STI in the last year | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.005 | 1.26 (1.07–1.47) | <0.001 | 1.66 (1.42–1.95) |

The variables of the history of imprisonment (OR=2.41, 95% CI: 2.13–2.72), the number of incarceration (OR=1.49, 95% CI: 1.35–1.65) and prison term (OR=1.67, 95% CI: 1.40–1.99), had a correlation with each other. The variable of history of imprisonment was entered into multivariate logistic regression model because of it's higher significant OR.

The variables of the history of drug use (OR=3.18, 95% CI: 2.70–3.75), and the history of drug injection (OR=2.33, 95% CI: 1.96–2.76) had a correlation with each other. The variable of history of drug use was entered into multivariate logistic regression model because of its higher significance OR.

The variables of the history of piercing during lifetime (OR=1.71, 95% CI: 1.40–2.09), and the history of piercing in prison (OR=1.67, 95% CI: 1.37–2.04), had a correlation with each other. The variable of the history of piercing during lifetime was entered into multivariate logistic regression model because of it's higher significant OR.

The variables of the history of extramarital sex during lifetime (OR=1.89, 95% CI: 1.56–2.29), the number of heterosexual/homosexual partners during the lifetime (OR=1.41, 95% CI: 1.28–1.55), and the condom usage (OR=1.18, 95% CI: 1.07–1.30) had a correlation with each other. The variable of the history of extramarital sex was entered into multivariate logistic regression model because of it's higher significant OR.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors associated with history of tattooing in prison among prisoners in 2015 and 2016.

| Variables | p-Value | AOR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1 | 1 | ||

| Male | 0.268 | 1.64 (0.67–4.04) | <0.001 | 2.27 (1.57–3.28) |

| Age (year) | ||||

| <35 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥35 | 0.200 | 1.21 (0.90–1.62) | 0.005 | 1.24 (1.07–1.44) |

| History ofimprisonmenta | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | <0.001 | 2.09 (1.63–2.69) | <0.001 | 2.54 (1.87–3.46) |

| History of drug use duringlifetimeb | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.019 | 1.79 (1.11–2.88) | <0.001 | 1.95 (1.53–2.48) |

| History of piercing in prison | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | <0.001 | 2.44 (1.56–3.80) | <0.001 | 2.47 (1.60–3.79) |

| History of extramarital sex during lifetime | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.005 | 1.51 (1.14–1.98) | 0.009 | 1.38 (1.09–1.75) |

The variables of the history of imprisonment (OR=2.54, 95% CI: 1.87–3.46), the number of incarceration (OR=1.37, 95% CI: 1.22–1.55) and prison term (OR=1.99, 95% CI: 1.46–2.70), had a correlation with each other. The variable of history of imprisonment was entered into multivariate logistic regression model because of it's higher significant OR.

The variables of the history of drug use (OR=1.95, 95% CI: 1.53–2.48), and the history of drug injection (OR=1.87, 95% CI: 1.18–2.96) had a correlation with each other. The variable of history of drug use was entered into multivariate logistic regression model because of it's higher significant OR.

The results of this study showed that the prevalence of tattooing during lifetime among prisoners was significant (47%). This is consistent with the results of Navadeh's study in Iran in 2009 (45%).11 International surveys show that this rate in Iran is less than that in many American countries (Brazil 66%,26 New York 59.5%)7 and Europe (Bosnia and Herzegovina 68.6%,13 Scotland 61%,27 Moldova 54%).28 According to the results of this study, the prevalence of tattooing in prisons is also significant (35%). There are no such reports this in other national studies.

However, comparing the studies from other countries shows that the prevalence of tattooing in Iran's prisons is much higher (American countries: Brazil 27.5%,8 Illinois 16%18 and European countries: Bosnia and Herzegovina 11%,21 Hungary 14%10). One of the reasons for the higher prevalence of tattooing in Iranian prisons can be the fact that, in this study, this rate was estimated among those with a history of tattooing, while in the above studies it was among prisoners participating in the study. In line with this, Akeke's12 and Hodzic's13 study show that the prevalence of tattooing in prison in inmates with a history of tattooing is 67% and 45%, respectively. However, this rate among prisoners with a history of tattooing was 16% in the Carnie's study27 and 3.7% in the Mahfoud's study.29

According to the results, the prevalence of tattooing during lifetime and in prison in high-risk groups is significantly higher. Consistent with the results of this study, the prevalence of tattooing during lifetime has been reported in many studies to be high in PWID.17,30,31 In this study, of PWID had a history of tattooing in their lifetime, and nearly half of them had done tattooing in prison. In addition, findings showed drug use was associated with tattooing during lifetime. The fact that tattooing19,32 and shared injection18 are both risk factors in the transmission of BBD, can increase the risk of transmission and the possibility of an outbreak of these diseases in the presence of both factors. With regard to this, implementation of harm reduction programs such as methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) is recommended to reduce the risk of drug injection and subsequently to reduce the prevalence of BBD in prisons.33

Other important results of this study showed that the prevalence of tattooing during lifetime and in prison was remarkable in sexually active subjects. According to the findings, the history of extramarital sex is associated with the prevalence of tattooing during lifetime. In Abiona's study, higher number of sex partners was associated with tattooing in prison.18 Given the relationship between tattoo and sex in the transmission of BBD in prison,34,35 the presence of both risk factors has a significant role in increasing the risk of disease transmission. Therefore, it is necessary to implement intervention programs to prevent or reduce extramarital sex at the community level.

The findings showed that more than 90% of tattoos were performed by non-professionals. Given the ban on tattooing in prisons, it is concluded that a notable percentage of tattooing is done with non-steril and shared equipment by unprofessional people. The results of studies by Ravlija21 and Akeke12 show that a significant number of tattooing in prisons are done by non-sterile instruments and non-professional people. Studies show that unprofessional tattooing plays an important role in the transmission of BBD.19,22 Accordingly, it is necessary to increase restrictions and supervision to prevent tattooing in prisons.

Considering that the study was cross-sectional, information and selection bias was one of the study's limitations. The following measures took place to reduce the bias: sampling was performed in one center, prisoners were selected based on the roster of prisoners in each prison, the interviewers were trained prior to the study, the data was recorded in Excel to maintain consistency and minimize human error in data entry and to make it possible for final integration of the data file at the national level, re-interviews were conducted with 3% of the samples of each prison, and 10% of the data entered into Excel was reviewed.

ConclusionThe results of this study showed that the prevalence of tattooing during lifetime and in prison were significantly high especially in high-risk groups such PWID and sexually active subjects. Given the role of tattooing, drug injection and extramarital sex in the transmission of BBD, harm reduction programs are recommended to reduce these high-risk behaviors in prisons.

Financial supportThis study was conducted under the financial support of the deputy of research and technology of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences.

Authors’ contributionsSaeede Jafari: Statistic analysis; approval of the final version of the manuscript; elaboration and writing of the manuscript; obtaining, analysis, and interpretation of the data.

Ghobad Moradi: Approval of the final version of the manuscript; conception and planning of the study; obtaining, analysis, and interpretation of the data; effective participation in research orientation; intellectual participation in the propaedeutic and/or therapeutic conduct of the studied cases; critical review of the literature; critical review of the manuscript.

Bushra Zareie: Statistic analysis; approval of the final version of the manuscript; elaboration and writing of the manuscript; obtaining, analysis, and interpretation of the data.

Mohammad Mehdi Gouya: Approval of the final version of the manuscript; conception and planning of the study; effective participation in research orientation; intellectual participation in the propaedeutic and/or therapeutic conduct of the studied cases; critical review of the literature; critical review of the manuscript.

Fatemeh Azimian Zavareh: Approval of the final version of the manuscript; conception and planning of the study; effective participation in research orientation; intellectual participation in the propaedeutic and/or therapeutic conduct of the studied cases; critical review of the literature; critical review of the manuscript.

Ebrahim Ghaderi: Statistic analysis; approval of the final version of the manuscript; conception and planning of the study; obtaining, analysis, and interpretation of the data; effective participation in research orientation; critical review of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

How to cite this article: Jafari S, Moradi G, Zareie B, Gouya MM, Zavareh FA, Ghaderi E. Tattooing among Iranian prisoners: results of the two national biobehavioral surveillance surveys in 2015–2016. An Bras Dermatol. 2020;95:289–97.

Study conducted at 19 provinces Alborz, Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari, East Azerbaijan, Fars, Gilan, Hamadan, Hormozgan, Kerman, Kermanshah, Khuzestan, Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad, Lorestan, Mazandaran, North Khorasan, Qazvin, Razavi Khorasan, Sistan and Baluchestan, Tehran, and Yazd, Iran.