Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by chronic ulcers due to an abnormal immune response. Despite the existence of diagnostic criteria, there is no gold standard for diagnosis or treatment. In Latin America, recognizing and treating pyoderma gangrenosum is even more challenging since skin and soft tissue bacterial and non-bacterial infections are common mimickers. Therefore, this review aims to characterize reported cases of pyoderma gangrenosum in this region in order to assist in the assessment and management of this condition. Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, and Chile are the countries in Latin America that have reported the largest cohort of patients with this disease. The most frequent clinical presentation is the ulcerative form and the most frequently associated conditions are inflammatory bowel diseases, inflammatory arthropaties, and hematologic malignancies. The most common treatment modalities include systemic corticosteroids and cyclosporine. Other reported treatments are methotrexate, dapsone, and cyclophosphamide. Finally, the use of biological therapy is still limited in this region.

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is an inflammatory disease, most commonly characterized by painful cutaneous ulcers with irregular, violaceous borders located on the lower limbs. It is frequently associated with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), inflammatory arthropathies, and hematologic malignancies.1,2 The worldwide incidence is estimated to be around two to three cases per 100,000 habitants per year,3 but this might be underestimated due to lack of a diagnostic gold standard. Pathogenesis is not well understood, but studies have suggested an abnormal immune response in patients with genetic predisposition, hence PG is classified within the spectrum of neutrophilic and auto-inflammatory syndromes.4,5

Other pathologic conditions in the clinical differential diagnosis – including infections, vasculitis/vasculopathy, and neoplastic disorders – should be ruled out with the assistance of laboratory testing, as well as histopathologic and microbiological studies.6 First-line treatment includes systemic corticosteroids and cyclosporine. Second-line and third-line therapeutic options comprise immunosuppressive, immunomodulatory, and biologic agents.7 The present study aimed to review the literature in order to recommend the best approach when facing patients with PG in Latin America (LA).

MethodsA systematic review was performed of the case-reports and case-series studies of PG from countries in LA published in MEDLINE (PubMed) and LILACS from inception to October 2018. The search strategies are available in Table 1.

Search strategy

| Database | PubMed: (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) Date: October 23rd, 2018. | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy | #1 | Search (chile OR brazil OR peru OR brasil OR colombia OR mexico OR ecuador OR venezuela OR uruguay OR cuba OR puerto rico OR costa rica OR latin america OR argentina) | 702779 |

| #2 | Search Pyoderma Gangrenosum[tiab] | 2853 | |

| #3 | Search (#1 AND #2) | 61 | |

| Database | LILACS (http://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/) Date: October 23rd, 2018. | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy | #1 | (tw:(pyoderma gangrenosum)) AND (instance:“regional”) AND (db:(“LILACS”)) | 141 |

PG is considered a rare disease of with estimated prevalence of two to three cases per 100,000 people and an adjusted incidence rate of 0.63 per 100,000 person-years. Risk of death is three times higher than general controls.8 It tends to have a slight predominance for females.8,9 Differences in comorbid conditions and differential diagnoses to consider vary significantly depending on geographic regions and local disease prevalence. Reports from LA are scarce and mostly consist of case reports or case series.10

PathogenesisNeutrophilic dysfunction has been implicated in the pathogenesis of PG.9 In addition, pathergy, which is defined as a nonspecific increase of neutrophil activity reaction, is present in other neutrophilic dermatoses (e.g., Behcet's disease and Sweet's syndrome) but it has been described in at least 30% of patients.11,12 Neutrophilic dysfunction shares the same pro-inflammatory effectors found in auto-inflammatory syndromes. Both are characterized by an over-activated innate immune system leading to the increased assembly of inflammasomes.2 Inflammasomes are responsible for the activation of the caspase 1, a protease that cleaves the pro-interleukin IL-1β into functionally active IL-1β. The overproduction of IL-1β triggers the release of several pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, inducing the recruitment and activation of neutrophils and subsequent neutrophil-mediated inflammation.5 IL-17 appears to be crucial in the recruitment of neutrophils in auto-inflammation and acts synergistically with tumor necrosis factor (TNF).13,14 Finally, IL-1β, IL-17, and TNF-α activate and increase the production of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which are overexpressed in the inflammatory infiltrate of PG, causing an inflammatory insult and the consequent destruction of the involved tissue.2,5

In conclusion, PG is the result of innate immune system over-activation via inflammasomes, coupled with the activation of the adaptive immune system, triggered by an external insult (e.g., pathergy) and/or a possible internal trigger in a genetically predisposed individual.15

Histopathologic findingsPG has non-specific histopathologic findings. Presence of perifollicular inflammation, edema, and neutrophilic inflammation are the initial features seen in untreated and expanding PG lesions. Polymorphonuclear leukocyte infiltration can lead to abscess formation and necrosis of the tissue with mixed inflammatory infiltrate. Additional findings may include giant cells, secondary thrombosis of small- and medium-sized vessels, and hemorrhage. Secondary leukocytoclastic vasculitis is present in around 40% of cases. Direct immunofluorescence also yields non-specific findings such as deposition of IgM, C3, and fibrin in the papillary and reticular dermal vessels. Due to the non-specific findings, skin biopsies are more useful to rule out other causes of ulceration that may present with similar clinical findings, such as infections, vasculitis, vasculopathies, or malignancies.12,16–18

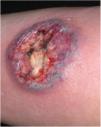

Clinical featuresPG is classified into four clinical subtypes: classic (ulcerative) (Figs. 1 and 2), bullous, pustular, and vegetative (Figs. 3 and 4). Ulcerative or classic PG often starts as an inflammatory erythematous violaceous pustule of a few millimeters in size, which enlarges forming an ulceration that gradually increases both in size and depth. The ulcer discharges a purulent and hemorrhagic exudate, easily detectable by applying pressure on its border. The purulent and malodorous exudate can be attributable to a bacterial colonization or to an actual superinfection. The border is well demarcated, elevated, and slowly progressive, with a violaceous color. An erythematous, edematous, and infiltrated halo extends up to 2cm from the border of the ulcer.2,5,19 The lesion is usually solitary, but multiple ulcers can occur; they are typically painful, ranging from a few millimeters to 30cm or more, localized mostly in extensor surface of the legs, but they can affect any anatomic site. They may be deep enough to expose tendons, fasciae, and muscles.5,20 Lesions start in healthy skin and may be provoked by trauma (pathergy). Therefore, postoperative PG (Figs. 5 and 6), peristomal PG, and worsening of lesions after sharp or surgical debridement frequently occur.21 The ulcer can propagate rapidly, showing a serpentine configuration.3,19 PG has been classically associated with inflammatory colitis (IBD and diverticulitis), hematological malignancies (myelodysplastic syndrome, monoclonal gammopathy, chronic myeloid leukemia, etc.), autoimmune inflammatory disease (seronegative polyarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis), and solid tumors (prostate and colon adenocarcinoma).4,8 Finally, sterile neutrophilic infiltrates have been found to affect internal organs supporting the concept of PG being a systemic disease.22

ResultsIn LA, 118 studies were found from 1981 to 2018, with 232 cases of PG. Brazil was the country with the largest report of case-series, with 96 (41.4%) cases of PG. The next highest total was from Argentina, which has 69 (29.7%) reported cases of PG, followed by Chile and Mexico, which have a similar number of reported cases, with 21 (9.1%) and 17 (7.3%), respectively. In addition, the results of the systematic review show that ulcerative PG was the most frequent type of PG reported, and that the others had similar prevalence. Bullous, vegetative (granulomatous), and pustular PG were reported in nine (3.9%), eight (3.5%), and five (2.1%) cases. The rest of PG cases did not report the subtype (Table 2).

Prevalence of Latin American pyoderma gangrenosum cases reported in the literature

| Total (n) | % | Ulcerative | Granulomatous | Pustular | Bullous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 96 | 41.38 | 76 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Argentina | 69 | 29.74 | 57 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Bolivia | 1 | 0.43 | 1 | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ |

| Chile | 21 | 9.05 | 20 | ‒ | 1 | ‒ |

| Colombia | 16 | 6.90 | 14 | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ |

| Costa Rica | 1 | 0.43 | 1 | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ |

| Cuba | 2 | 0.86 | 1 | 1 | ‒ | ‒ |

| Mexico | 17 | 7.33 | 5 | 1 | ‒ | ‒ |

| Paraguay | 1 | 0.43 | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ | 1 |

| Peru | 5 | 2.16 | 2 | ‒ | 1 | 2 |

| Venezuela | 3 | 1.29 | 2 | 1 | ‒ | ‒ |

| TOTAL | 232 | 100 | 179 | 8 | 5 | 9 |

| % | 100 | ‒ | 77.16 | 3.45 | 2.16 | 3.88 |

In addition, the systematic review found that there was a high prevalence of PG cases associated with comorbidities. Overall, 149 (64.5%) and 37 (16%) of the patients included in the analysis had PG associated to a condition or surgery, respectively. In the rest of PG patients, no other conditions or disease associations were reported. IBD was the most frequent conditions associated (53/149, 35.6%), then ulcerative colitis (UC) (32/149, 21.5%) and Crohn's disease (10/149, 6.7%). Other inflammatory diseases were also frequent (54/149, 36.2%); among them, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (17/149, 11.4%), antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) (15/149, 10.1%), systemic erythematous lupus (4/149, 2.7%), and Takayasu's arteritis (4/149, 2.7%) were reported. Several malignances were reported in association with PG (19/149, 12.8%), in particular hematologic malignancies (14/149, 9.4%) and solid-organ malignancies (5/149, 3.4%). Other conditions were also reported (23/149, 15.4%), including the presence of pulmonary nodules (5/149, 3.4%) of unknown etiology. In regard to surgical procedures, reduction mammoplasty (9/149, 6.0%), laparotomy (6/149, 4.0%), and skin grafting (4/149, 2.7%) were the more frequent triggers of PG. It is important to mention that due to the limited information in the reports and the scarce number of PG cases, only descriptive statistical analysis was performed (Table 3).

Prevalence of the conditions associated with pyoderma gangrenosum reported in the Latin American literature

| Condition | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| IBD | ||

| No specified | 11 | 7.4 |

| UC | 32 | 21.5 |

| CD | 10 | 6.7 |

| Subtotal | 53 | 35.6 |

| Malignancy | ||

| Hematologic malignancy | 14 | 9.4 |

| Solid-organ malignancy | 5 | 3.4 |

| Subtotal | 19 | 12.8 |

| Inflammatory | ||

| Antiphospholipid syndrome | 15 | 10.1 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 17 | 11.4 |

| Lupus erythematosus | 4 | 2.7 |

| Takayasu's arteritis | 4 | 2.7 |

| Other | 14 | 9.4 |

| Subtotal | 54 | 36.2 |

| Other conditions | ||

| Pulmonary nodules | 5 | 3.4 |

| Cocaine consumption | 2 | 1.3 |

| Diverticular disease | 2 | 1.3 |

| Pregnancy | 2 | 1.3 |

| Other | 12 | 8.1 |

| Subtotal | 23 | 15.4 |

| Total | 149 | 64.5a |

| Secondary to surgery | ||

| Reduction mammoplasty | 9 | 22.5 |

| Laparotomy | 6 | 15.0 |

| Abdominoplasty | 4 | 10.0 |

| Skin grafts | 4 | 10.0 |

| Total surgery | 37 | 16.0b |

Thus, the systematic review of PG case-series from LA helped to elucidate the main associated conditions. In Table 4, all the studies where PG was reported to be associated with clinical or surgical conditions are listed.

Conditions associated with pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) reported in the Latin American literature

| n | Author | Year | Country | Number of patients | Clinical type | Associated disease | Secondary to surgery or drugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Corti et al.59 | 1981 | Argentina | 1 | Ulcerative | Crohn's disease | No |

| 2 | Della-Giovanna et al.60 | 1991 | Brazil | 4 | Ulcerative | Two patients with ulcerative colitis, one with pregnancy | No |

| 3 | Moreno et al.61 | 1994 | Argentina | 2 | Ulcerative | Two patients with rheumatoid arthritis | No |

| 4 | Vignale et al.62 | 1996 | Argentina | 4 | Ulcerative | Three patients with Crohn's disease, two with seronegative arthritis, and one with ulcerative colitis | No |

| 5 | Saraceno et al.63 | 2002 | Argentina | 6 | Ulcerative | One patient with myelodysplastic syndrome, one with rheumatoid arthritis, one with hemophagocytic syndrome and hepatitis C | No |

| 6 | Plaza64 | 2004 | Argentina | 1 | Ulcerative | Rheumatoid arthritis | No |

| 7 | Simon et al.65 | 2005 | Argentina | 1 | Ulcerative | Ulcerative colitis | Peristomal after total colectomy |

| 8 | Vazquez et al.66 | 2009 | Argentina | 1 | Ulcerative | Chronic osteomyelitis | Knee prosthesis replacement |

| 9 | Sommerfleck et al.67 | 2014 | Argentina | 1 | Not reported | Ulcerative colitis | No |

| 10 | Achenbach et al.68 | 2014 | Argentina | 1 | Ulcerative | Crohn's disease | Sulfasalazine |

| 11 | Curmona et al.69 | 2014 | Argentina | 2 | Ulcerative | One patient with metastatic ovarian cancer | Abdominal tumor resection |

| 12 | Pereyra et al.70 | 2014 | Argentina | 1 | Ulcerative | Renal transplant | No |

| 13 | Fassi et al.71 | 2015 | Argentina | 1 | Ulcerative | Rheumatoid arthritis and ulcerative colitis | No |

| 14 | Silva-Feistner et al.72 | 2015 | Argentina | 1 | Ulcerative | None | Cesarean |

| 15 | Galimberti et al.73 | 2016 | Argentina | 1 | Ulcerative | Ulcerative colitis | No |

| 16 | Vacas et al.1 | 2017 | Argentina | 27 | Ulcerative | Ten patients with IBD, seven with hematologic malignances, five with rheumatoid or seronegative arthritis, and one with cocaine consumption | No |

| 2 | Bullous | ||||||

| 2 | Pustular | ||||||

| 17 | Vega et al.74 | 2018 | Argentina | 1 | Ulcerative | Retroperitoneal fibrosis | Exploratory mid-laparotomy |

| 18 | Vacas et al.75 | 2018 | Argentina | 1 | Bullous | Acute and chronic myeloid leukemia | No |

| 19 | Pires et al.76 | 1987 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Chronic hepatitis | No |

| 20 | Lana et al.77 | 1990 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Multiple sclerosis | No |

| 21 | Pessato et al.78 | 1996 | Brazil | 9 | Not reported | Five patients with comorbidities | No |

| 22 | Souza et al.79 | 1999 | Brazil | 11 | Predominantly ulcerative | One patient with ulcerative colitis, one with rheumatoid arthritis, one with Grave's disease, one with diabetes mellitus | No |

| 23 | Cabral et al.80 | 2004 | Brazil | 4 | Ulcerative | Four patients with ulcerative colitis, one with additional primary sclerosing cholangitis, one with seronegative arthritis | No |

| 24 | Martinez et al.81 | 2005 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Ulcerative colitis | No |

| 25 | Costa et al.82 | 2005 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Rheumatoid Arthritis | No |

| 26 | Fraga et al.83 | 2006 | Brazil | 1 | Superficial granulomatous | Psoriasis | No |

| 27 | Coltro et al.84 | 2006 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative in donor site | None | Skin graft for varicose ulcers |

| 28 | Batista et al.85 | 2006 | Brazil | 1 | Bullous | Myelodysplastic syndrome | No |

| 29 | Meyer et al.86 | 2006 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Crohn's disease | Infraumbilical median laparotomy |

| 30 | Franca et al.87 | 2006 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Gastric adenocarcinoma | No |

| 31 | Burkieviecz et al.88 | 2007 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Systemic lupus erythematosus/antiphospholipid syndrome | No |

| 32 | Barbato et al.89 | 2008 | Brazil | 13 | Ulcerative | Two patients with Crohn's disease, two with diabetes, two with collagenosis, one with leukemia. | No |

| 2 | Superficial granulomatous | ||||||

| 1 | Bullous | ||||||

| 33 | Tinoco et al.90 | 2008 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Acne | Isotretinoin |

| 34 | Dornelas et al.91 | 2008 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | None | Reduction mammoplasty and abdominoplasty |

| 35 | Bonamigo et al.92 | 2008 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | None | Breast implant with silicone prosthesis and facial surgery |

| 36 | Coelho et al.93 | 2009 | Brazil | 2 | Ulcerative | Inflammatory arthritis/splenomegaly | No |

| 37 | Berbert et al.94 | 2009 | Brazil | 1 | Superficial granulomatous | None | Donor site after skin grafting for burns. |

| 38 | Furtado et al.95 | 2010 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | None | Reduction mammoplasty and abdominoplasty |

| 39 | Avelar et al.96 | 2011 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Breast cancer | Breast quadrantectomy and radiotherapy |

| 40 | Fonseca et al.97 | 2011 | Brazil | 1 | Bullous | Ulcerative colitis | No |

| 41 | Grillo et al.98 | 2012 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | None | Reduction mammoplasty |

| 42 | Maia et al.99 | 2012 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Cocaine use | No |

| 43 | Cunha et al.100 | 2012 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | None | Laparoscopy |

| 44 | Bittencourt et al.101 | 2012 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Pulmonary nodules | No |

| 45 | Andrade et al.102 | 2012 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Inflammatory bowel disease | No |

| 46 | Carvalho et al.103 | 2013 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Splenic and renal impairment | No |

| 47 | Kruger et al.104 | 2013 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Ulcerative colitis | No |

| 48 | Soares et al.105 | 2013 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | None | Reduction mammoplasty and abdominoplasty |

| 49 | Beber et al.106 | 2014 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Rheumatoid arthritis | No |

| 50 | Marchiori et al.107 | 2014 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Pulmonary nodules | No |

| 51 | Rosseto et al.108 | 2015 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | None | Abdominoplasty |

| 52 | de Souza et al.109 | 2015 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Myelodysplastic syndrome | No |

| 53 | Sempertegui et al.110 | 2015 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Breast cancer | Breast quadrantectomy and radiotherapy |

| 54 | Soncini et al.111 | 2016 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | None | Augmentation mastopexy |

| 55 | Dantas et al.55 | 2017 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Autoimmune hepatitis | No |

| 56 | Freitas et al.112 | 2017 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Iliac vein compression syndrome | No |

| 57 | Gabe et al.113 | 2018 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Pyogenic arthritis | No |

| 58 | Bittencourt et al.114 | 2018 | Brazil | 1 | Ulcerative | Multiple myeloma | Autologous stem cell transplantation and then laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

| 59 | Clemente et al.115 | 2018 | Brazil | 2 | Ulcerative | Two patients with atypical Takayasu's arteritis | No |

| 60 | Perez et al.116 | 2001 | Chile | 2 | Ulcerative | None | Cesarean |

| 61 | Lopez de Maturana et al.54 | 2001 | Chile | 3 | Ulcerative | Two patients with diverticular disease, one patient with Crohn's disease, one patient with rheumatoid arthritis | No |

| 1 | Pustular | ||||||

| 62 | Hevia et al.117 | 2004 | Chile | 1 | Ulcerative | Ulcerative colitis | Peristomal after total colectomy |

| 63 | Eulufi et al.118 | 2006 | Chile | 3 | Ulcerative | None | Two patients after skin graft, one patient after reduction mammoplasty |

| 64 | Calderon et al.119 | 2011 | Chile | 1 | Ulcerative | Ulcerative colitis | No |

| 65 | Fernandez-Castillo et al.120 | 2012 | Chile | 1 | Ulcerative | Wegener granulomatosis/chronic kidney disease | Arteriovenous fistula |

| 66 | Gosch et al.121 | 2012 | Chile | 1 | Ulcerative | None | Reduction mammoplasty |

| 67 | Melo and Fernandez 122 | 2013 | Chile | 1 | Ulcerative | None | Foot and ankle surgery |

| 68 | Calderon et al.123 | 2013 | Chile | 3 | Ulcerative | None | After reduction mammoplasty |

| 69 | Bannura et al.124 | 2014 | Chile | 1 | Ulcerative | Ulcerative colitis | Laparotomy/ileostomy |

| 70 | Erlij et al.125 | 2018 | Chile | 1 | Ulcerative | Erythema induratum and large B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | No |

| 71 | Penaloza et al.126 | 1988 | Colombia | 1 | Ulcerative | Ulcerative colitis | No |

| 72 | Restrepo et al.127 | 2006 | Colombia | 2 | Ulcerative | Two patients with ulcerative colitis | No |

| 73 | Jaime-Lopez et al.128 | 2009 | Colombia | 1 | Ulcerative | Ulcerative colitis | Infliximab |

| 74 | Cañas et al.129 | 2010 | Colombia | 7 | Ulcerative | Seven patients with antiphospholipid syndrome | No |

| 75 | Cadavid et al.130 | 2012 | Colombia | 1 | Ulcerative | Ulcerative colitis | None |

| 76 | Severiche et al.131 | 2014 | Colombia | 1 | Ulcerative | Breast phyllodes tumor (paraneoplastic) | No |

| 77 | Acon-Ramirez et al.132 | 2017 | Costa Rica | 1 | Ulcerative | Rheumatoid arthritis | No |

| 78 | Moreira-Preciado et al.133 | 2001 | Cuba | 1 | Superficial granulomatous | Renal failure | No |

| 79 | Hernandez-Urra et al.134 | 2010 | Cuba | 1 | Ulcerative | Ulcerative colitis | No |

| 80 | Zonana-Nacach et al.135 | 1994 | Mexico | 2 | Not reported | Two patients with rheumatoid arthritis | No |

| 81 | Reynoso-von Dratein et al.58 | 1997 | Mexico | 9 | Not reported | Three patients with rheumatoid arthritis and two patients with systemic lupus erythematosus | No |

| 82 | Chacek et al.136 | 1998 | Mexico | 1 | Ulcerative | Inferior cava vein syndrome due to thrombosis and antiphospholipid syndrome | No |

| 83 | Muñiz-Gonzalez et al.137 | 2007 | Mexico | 1 | Ulcerative | Ulcerative colitis, diverticular disease | No |

| 84 | Contreras-Ruiz et al.138 | 2008 | Mexico | 1 | Ulcerative | Rheumatoid arthritis | No |

| 85 | Barrera-Vargas et al.139 | 2015 | Mexico | 2 | Ulcerative | Two patients with pulmonary nodules and Takayasu's arteritis | No |

| 86 | Contreras-Verduzco et al.140 | 2018 | Mexico | 1 | Superficial granulomatous | Pulmonary nodules and nodular scleritis | No |

| 87 | Real-Delor et al.141 | 2011 | Paraguay | 1 | Bullous | Ulcerative colitis | No |

| 88 | Dominguez et al.142 | 2009 | Peru | 1 | Pustular | Ulcerative colitis | No |

| 89 | Carrillo-Nanez et al.143 | 2014 | Peru | 1 | Bullous | Ulcerative colitis | No |

| 90 | Deza-Araujo et al.144 | 2014 | Peru | 1 | Ulcerative | Systemic lupus erythematosus | No |

| 91 | Fermin et al.145 | 1989 | Venezuela | 2 | Ulcerative | One patient with ulcerative colitis | No |

| 92 | Valecillos et al.146 | 1998 | Venezuela | 1 | Superficial granulomatous | Pregnancy | No |

In general, ulcerative entities resembling PG fall into one of six disease categories: (a) primary deep cutaneous infections (e.g., sporotrichosis, cutaneous tuberculosis, leishmaniasis, etc.) (Figs. 7 and 8); (b) vascular occlusive or venous disease (e.g., APS, venous stasis ulceration, etc.); (c) vasculitis (e.g., Wegener's granulomatosis, polyarteritis nodosa, etc.); (d) malignant processes involving the skin (e.g., angiocentric T-cell lymphoma, anaplastic large-cell T-cell lymphoma, etc.); (e) drug-induced or exogenous tissue injury (factitial disorder, loxoscelism, etc.); and (f) other inflammatory disorders (cutaneous Crohn's disease, ulcerative necrobiosis lipoidica, etc.). However, in LA, the most common differential diagnoses include deep cutaneous infections, vascular occlusive disease, and metabolic disorders.23 It is crucial for the management of PG in this region to rule out infection, as immunosuppressive medications used to treat PG may be contraindicated in these patients.24 Depending on the specific region, infectious ulcers can be caused by Leishmania parasites, atypical Mycobacterium species, deep fungal infections (sporotrichosis, chromoblastomycosis and, mycetoma), myasis, and cutaneous amebiasis.3

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is a common skin disease in developing countries, such as Brazil and Peru.25 Lesions may start as a papule or a nodule that develops into an ulcer with or without a scar (Figs. 7 and 8). They are usually painless, but when painful, secondary infection is generally present. The initial diagnosis of CL is based on the clinical presentation and the patient's history of visiting an endemic area. Diagnostic work up includes multiple components in order to provide the highest likelihood of confirmation. Biopsy specimens should be obtained for impression smears, histopathologic slides with hematoxylin and eosin, Giemsa stain and special stains for other microbes, culture, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis if diagnosis is challenging.26

Ulcerating cutaneous lesions can be caused by mycobacterial infections including Mycobacterium ulcerans, M. marinum, and M. tuberculosis. M. ulcerans is the third most common agent of mycobacterial disease (after tuberculosis and leprosy) and the most common mycobacterium causing cutaneous ulceration.27 Buruli ulcers, which are caused by M. ulcerans, are endemic in foci in West Africa and have been reported as an imported disease in countries of LA such as Peru, Brazil, Guiana, and Mexico.28 Microscopy and PCR are used for routine diagnosis, while culture is less useful given time requirements and lack of species specificity.29 Treatment is generally surgical, although a combination of rifampicin and streptomycin may be effective in the early stage.

Cutaneous tuberculosis (CTB) is an infection caused by M. tuberculosis complex, M. bovis, and in immunocompromised hosts, by bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination.30 An increase in its incidence has been described in several countries of LA in recent years, especially in urban centers and regions with high prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Lupus vulgaris is a form of CTB that initiates as smoldering papular or tuberous lesions and progresses to plaques with necrosis and ulceration, with or without cicatricial deformities and mutilations.31 Diagnostic approaches to CTB include skin biopsy with acid fast bacilli stain and culture, as well as PCR amplification testing of biopsy tissue.32

Sporotrichosis is one of the most common deep mycoses; it may be accompanied by ulceration.33 Most cases of sporotrichosis are currently being reported in South and Central America, with recent outbreaks transmitted by cats.34 The primary cutaneous lesions may appear as papular, nodular, or pustular lesions that develop into either a superficial ulcer or a verrucous plaque. During progression, the lymphocutaneous form displays multiple subcutaneous nodules that are formed along the course of locally draining lymphatics (sporotrichoid spread). In contrast, the localized form shows no lymphatic spread and is characterized by indurated or verrucous plaques and occasional ulcers.35,36 Diagnosis of sporotrichosis is primarily clinical due to its distinguished presentation, but in difficult cases, culture is the gold standard.37Sporotrichosis is treated with systemic itraconazole.38

Mycetoma is a chronic subcutaneous fungal infection caused by inoculation via organic matter such as splinters or thorns. Given the ubiquitous nature of causative fungi, there may be a genetic predisposition to developing the disease.39 In South America, the most common pathogens are Trematosphaeria grisea, Madurella mycetomatis, and Scedosporium apiospermum. The clinical manifestations of mycetoma include painless slow growing subcutaneous nodules, which may evolve into necrotic abscesses with sinus tracts. Lesions are most commonly located on exposed areas, especially the lower extremities. The expression of black granules and debris from the lesions is highly suggestive of fungal mycetoma.40 Diagnostic work up includes tissue microscopy using potassium hydroxide, as well as deep tissue biopsies for culture on Sabouraud dextrose agar kept at both room temperature and 37°C. As fungal cultures can take several weeks, histopathologic evaluation may expedite the diagnosis but may not aid in identifying the causative species.

Furuncular myiasis is most commonly caused by larval tissue penetration by Dermatobia hominis, the botfly, and Cordylobia anthropophaga, the tumbu fly. Lesions slowly evolve into periodically painful nodules. They may present with multiple nodules containing larvae, and removal of the larvae typically relieves symptoms.

Cutaneous amebiasis is a rare extracutaneous manifestation of Entamoeba histolytica infection. It can occur independently through direct inoculation or along with other tissue involvement. There is predilection of the disease in the perineal region due to direct inoculation from stool, leading to ulcerations, but lesions can be present anywhere on the body.41 Notable clinical features include one or more painful and malodorous ulcers with a necrotic base.42 The edges of the lesions are often raised and red in color. Progression of the ulcers is often rapid, with destruction in all planes.42 Confirmation of the diagnosis can be made with identification of the pathogen on tissue biopsy of the ulcer. Cytologic smears may also be useful in identifying the trophozoites.42

Chromoblastomycosis infection is causes by fungal spore implantation into the skin at sites of trauma. The fungus is ubiquitous in the soil and vegetation and therefore is highly associated with trauma occurring in the outdoors.43,44 This inoculation leads to a chronic granulomatous reaction. The infection initially begins as an inflamed macule, which evolves into a papule and eventually develops into one of several morphologic subtypes, including nodular, verrucous, tumorous, cicatricial, or plaque types.45 Disease progression is very slow and is usually limited to the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Due to the mechanism of inoculation, it most commonly occurs on the lower extremities. One rare complication in chronic lesions is squamous cell carcinoma transformation.44,45 Diagnosis is made by identifying muriform cells on microscopy.44–48 Samples can be obtained via scrapings, tape preparation, wet mounts, tissue biopsy, or culture. Treatment is dependent on the stage at diagnosis; early lesions can be treated effectively with surgery or cryotherapy. Pharmacologic treatment options are systemic antifungals for refractory or extensive disease.44,47,49

Treatment of PG in LAThere is no gold standard therapy for PG, but treatment should be guided by extension and depth of the ulcer, associated systemic diseases, the patient's performance status, and availability of medications.3,50 Topical therapy is the first choice for small lesions in the early stages (papules, pustules, nodules, or superficial ulcers). It includes dressings, topical immunomodulators, and intralesional corticosteroid injections.51 A report from Chile showed an excellent and rapid respond to cyclosporin 5%, clobetasol 0.05%, and gentamycin 0.2% ointment applied twice daily, after 18 weeks.52

In patients with severe forms of PG, or with rapid expansion and resistance to topical treatment, systemic therapy is the treatment of choice. Corticosteroids are the first line drugs in the acute phase and should be initiated at high doses (1–2mg/kg).3,53 A steroid-sparing drug should be used in the initial phases to minimize long-term steroid toxicity and side effects. Agents including dapsone, sulfasalazine, methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, and biologics may be employed.2,53

In LA, systemic corticosteroids are, by far, the most frequent first-line therapy. In a cohort of patients with PG, systemic corticosteroids were administered to 87% of patients (n=27), at a dose-range of 1–1.5mg/kg/day, for two to 14 months.1 In another cohort, these drugs were initiated in 81.8% of the patients (n=9); after 60 months, only two patients had been recurrence free, while the others had multiple recurrences, treated with sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim, minocycline, topical corticosteroids, and cyclophosphamide.54 In addition, corticosteroids and local treatment were preferred when PG was associated with autoimmune diseases, such as autoimmune hepatitis.55

Cyclosporine is less frequently used as a first-line therapy due to its side effects. Cyclosporine monotherapy induces a rapid remission of the disease at a dose of 3–5mg/kg/day after a few weeks of treatment and complete resolution of the lesion after one to three months, but long-term therapy might be problematic.3 In one report from LA, it was used in 13% (n=4) of the patients, for one to six months, with a dose of 1.5–3mg/kg/day, with no relapses after four years of treatment.1

Experience with methotrexate in LA is scarce, and it is generally used as a steroid-sparing drug in severe or refractory disease.56 However, a case report from Chile showed a remarkable response with intralesional methotrexate. After 40 days of oral prednisolone, followed by eight weeks of 10mg weekly intramuscular methotrexate, the PG ulcers failed to improve. After seven injections of methotrexate (25mg/week) administered intralesionally in the erythematous border of the ulcers, almost 90% of the ulcer was healed.57

In Mexico, an open-label trial assessed intravenous bolus cyclophosphamide in a dose of 500mg/m2 of body surface area monthly for a total of three or six doses in nine patients with PG. Seven patients had complete remission, one experienced failure, one had partial remission, and three had relapses after three and twelve months.58 However, rare but severe side effects, such as infertility, hemorrhagic cystitis, and secondary tumors, might limit its use.3

Dapsone and sulfasalazine were reported only in two patients with PG in Chile.54 However, recurrence occurred on multiple occasions and each patient was eventually transitioned to systemic steroids and cyclosporine.

For steroid-resistant PG, biological agents are now increasingly used in LA. TNF-α inhibitors are preferred due to availability and long-term safety data, but the high cost of these medications is still a limitation in this region.

ConclusionBased on the current studies, PG in LA is still an under-reported disease and there is a lack of robust studies. The most frequent form of PG is the ulcerative subtype, which is most commonly associated with IBD. An accurate diagnosis in LA is even more challenging, as the prevalence of cutaneous infections that mimic all forms of PG is higher compared to developed countries. Being aware of the epidemiological variations of infectious diseases might provide clinical clues in the diagnosis of PG-like lesions, not only in people from these areas but also in immigrants and travelers. Treatment of PG is primarily with systemic corticosteroids; however, some positive outcomes have been reported with cyclosporine and methotrexate. In LA, biological therapy data is scarce and apparently reserved for severe forms of PG non-responsive to steroids due to high cost and limited access.

Financial supportNone declared.

Author's contributionsMilton José Max Rodríguez-Zúñiga: Approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Michael Heath: Approval of the final version of the manuscript.

João Renato Vianna Gontijo: Approval of the final version of the manuscript; composition of the manuscript.

Alex G. Ortega-Loayza: Approval of the final version of the manuscript; composition of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

How to cite this article: Rodríguez-Zúñiga MJM, Heath MS, Gontijo JRV, Ortega-Loayza AG. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review with special emphasis on Latin America literature. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:729–43.

Study conducted at the Oregon Health and Sciences University, Portland, United States; and at the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.